The Great Cruise Ship Bazaar

Cruise Ships Delivered, Sold and Scrapped During the Pandemic

Scroll down to view infographic

Updated October 27, 2021

Text & Infographic by Joseph Slattery

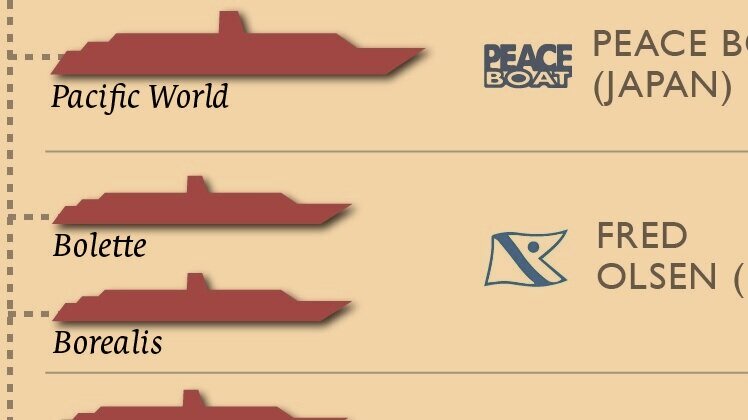

This infographic is part of a series of articles and graphics dealing with the post-pandemic future of the cruise industry. The first, Armageddon, offers perspective on the state of the industry when the pandemic began. Out of Hibernation is a top-line capacity assessment of world’s ten leading cruise lines, pre- and post-pandemic. The infographic Taking Inventory compares post-pandemic fleets of major brands by size and bed-age. The Great Cruise Ship Bazaar is a visual explanation of what was going on behind the scenes during 2020 and 2021, mapping out in detail a Byzantine-like maze of transactions involving 59 different ships that have at least 450 lower berths. Angle of Ascent is the last in the series, offering a framework for industry capacity growth in the five years 2022-2026, brand-by-brand based on contracted newbuilds and potential divestitures.

Out of Hibernation illustrates what some find to be a surprising fact. Throughout the pandemic, both consumer and trade media emphasized events that implied an industry down-sizing. For example, several well-known outlets, including The New York Times, have run stories about ships beached and dismantled at scrapyards in Turkey and India. Within the financial community, Carnival Corporation repeatedly emphasized the divestiture of 19 ships from its nine-brand fleet. These ships represented 13% of pre-pandemic capacity but contributed only 3% of fiscal 2019 operating income, according to company SEC filings. But overall, driven by the unrelenting pace of newbuild deliveries, the top-ten brands will have actually gained capacity during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021.

While these mega-brands represent around three-quarters of global capacity, their activity does not fully represent the industry as a whole. The cruise industry is growing a longer tail. The top-ten claimed all but two of 13 largest newbuilds to be delivered in 2020 and 2021 (the exceptions are Virgin Voyages’ Scarlet Lady and Valiant Lady), but of the 18 ships scrapped, only four came directly from top-10 fleets. Of the 22 ships sold in the second-hand market and not scrapped, the top-ten sold 17 and bought none. Carnival Corporation assigned four ships as hand-me-downs -- two from Princess to sister brand P&O Australia and two more from Costa to its joint venture with the China State Shipbuilding Corporation. Another Princess ship was sold to Sanya International Cruise Development, a new Chinese operation to be managed in part by industry veteran V.Ships Leisure.

The Bazaar’s largest and busiest tent was that of Carnival Corporation. Some operators, like NCL Holdings and MSC, didn’t show up at all. The most active of the second-hand buyers has been the Greek ferry operator Seajets, snatching up four 1990’s-era liners including Holland America Line’s Maasdam, Ryndam and Veendam, and the ex-Royal Caribbean Majesty of the Seas. Seajets also bought P&O’s Oceana -- originally called Ocean Princess when delivered to sister- brand Princess Cruises in 2000. These vessels do not fit into Seajets current ferry operating model, so their long-term fate is open to speculation.

In addition to two single-ship transactions, Royal Caribbean Group sold one of its four brands lock, stock and barrel. Sycamore partners, a leading New York-based private equity firm with no cruise management experience, bought Azamara Cruises and its three-ship fleet for a reported $201 million in cash. Sycamore quickly upped the ante by purchasing a fourth ship, the Pacific Princess (and sister to the other three) from Carnival Corporation.

Of the 18 ships scrapped, seven came directly or indirectly from pandemic-induced insolvencies, including four of the five ships operated by Britain’s Cruise & Maritime Voyages and all three ships operated by Pullmantur, a Spanish brand minority-owned by Royal Caribbean Group.

Generally speaking, scrap metal is an industry not often touched by sentimentalism. When cruise ships go to the graveyard, it is usually unnoticed, sparing a pang of melancholy to the millions who hold fond memories — a romance, an anniversary, new friends, a family reunion, or just a great vacation. The tired, rusted hulls beached on Turkish or Indian shores usually bear unfamiliar names, like the Ocean Dream, a.k.a. Tropicale — Carnival’s first purpose-built ship launched in 1981, and the Magellan, a.k.a. Holiday, a star in the Kathie Lee “Ain’t We Got Fun” campaigns of the 80’s. The Renzo Piano-designed Crown Princess with her dolphin profile, a symbol of Princess Cruises in the 1990’s, was beached in disguise as Karnika. Arguably the most iconic of all was Sovereign of the Seas. She was, in her 1988 debut, the largest and most spectacular vessel ever built for cruising. When scrapped last year on the shores near Aliaga, Turkey, the name Sovereign, -- without the “of the Seas” -- was visible on her fantail.

What’s the net of all this? Not including the Azamara transaction, 59 ships have been — or are expected to be -- delivered, sold, or scrapped in 2020 and 2021. At one end of the pipe, 19 new ships added over 58,000 lower berths to global cruise inventory, while at the other end, the 18 scrapped ships removed over 26,000 berths.

I mentioned the cruise industry’s long tail. In addition to the nineteen 19 deliveries (qualified by 450 or more lower berths) shown on this graphic, at least 18 smaller newbuilds have been or will be added to the global fleet in 2020 and 2021, primarily in the expedition segment. An impressive flotilla, but combined they represent only around 3,500 lower berths — less than the capacity of the Enchanted Princess.